The recent heatwaves in the Western US have made everyone sit up and take notice.

With multiple days and weeks of triple-digit temperatures during late June and July, the heat continues to dominate national and international headlines.

Hundreds of temperature records were set in typically hot areas in California and Arizona, and in regions unaccustomed to extreme heat, such as the Pacific Northwest, where many buildings don’t even have air conditioning.

The heatwaves caused hundreds of deaths, scorched crops, canceled flights, warped train tracks, and buckling roads.

While the devastating impact of heat is nothing new—heat is the leading cause of U.S. weather fatalities over the past 30 years according to the National Weather Service— most scientists agree that climate change is behind this new wave of unprecedented heat. And this trend of intense heat waves is likely to continue to have a serious impact on health.

While nations work to address the longer-term mitigation of and adaptation to climate change, what can people and business leaders concerned about the health of their employees do about it? Here are five takeaways and tools that can help us better understand and cope with the day-to-day impacts of extreme heat on health and wellness already occurring today.

1. Hot Car Deaths of Kids and Pets

This is number one for a reason because it is one of the most heartbreaking and avoidable impacts of extreme heat. Nearly 900 children have died since 1998 while left unattended in a hot vehicle according to NoHeatStroke.org, a website maintained by meteorologist Jan Null. Seven deaths have already occurred this year. Dozens of pets also die every year after being left in hot vehicles or outdoors in extreme heat according to PETA.

While many of these deaths occur when the outdoor temperature is 90 degrees or higher, some have happened with outdoor temperatures as cool as the 70s. That’s because the interior temperature of a vehicle can rise nearly 20 degrees in 10 minutes, nearly 30 degrees in 20 minutes, and nearly 50 degrees in one to two hours.

The Hot Cars Act of 2021, which recently passed in the U.S. House of Representatives, would require all new passenger motor vehicles “to be equipped with a system that detects the presence of an unattended occupant in the passenger compartment of the vehicle and engages a warning to reduce death and injury resulting from vehicular heatstroke, particularly incidents involving children.” The bill would become law if it passes the Senate and is signed by the President, though similar legislation has failed to win approval in recent years.

In the meantime, safety recommendations at NoHeatStroke.org implore adults to “never leave a child unattended in a vehicle … be sure that all occupants leave the vehicle when unloading … don’t overlook sleeping babies … always lock your car and ensure children do not have access to keys or remote entry devices.” KidsandCars.org outlines a similar checklist of safety tips for parents and caregivers.

2. Heat and Humidity Levels “Above Humans’ Survivability Limit”

Climate models predict that the combination of heat and humidity could reach deadly levels by the middle of the 21st century. But new research shows that some locations are already reporting heat and humidity extremes above humans’ survivability limit decades earlier than expected.

“I believe that humid heat is the most underestimated direct, local risk of climate change,” said Radley Horton, a Columbia University professor and co-author of the study, in a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration article summarizing the research.

Our bodies cool off by sweating, but only if the water evaporates. At extremely high levels of heat and humidity “there is so much moisture in the air that sweating becomes ineffective at removing the body’s excess heat,” explained Colin Raymond, a scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and lead author of the study. “At some point, perhaps after six or more hours, this will lead to organ failure and death in the absence of access to artificial cooling.”

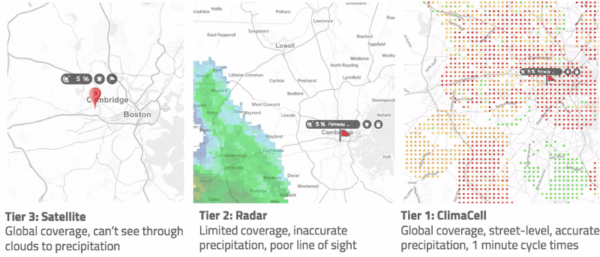

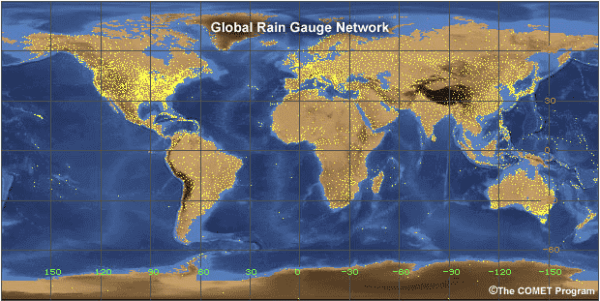

The heat index is the most common way meteorologists communicate the combination of heat and humidity, but it only reflects the temperature as measured in the shade. Anyone responsible for the safety of outdoor workers, outdoor athletes, or children playing outside should be aware of the Wet Bulb Globe Temperatures (WBGT), which is measured in the sun and takes into account temperature, humidity, cloud cover, and other variables.

The National Weather Service provides the current and forecast WBGT across the United States. Here is one example of athletic activity guidelines (such as how often to take water and rest breaks) based on WBGT, although guidelines vary by geography since people’s response to heat varies by region.

3. Heat is an Issue of Racial Inequity

Extreme heat disproportionately impacts people of color due to racist housing policies of the 1930s that concentrated Black people and other people of color in urban heat islands, and then rated those neighborhoods as too “risky” to insure mortgages. As detailed in a New York Times story, this led to a lack of investment in these “redlined” neighborhoods and the results are still felt today in many ways, including temperatures that can be as much as 20 degrees hotter than surrounding areas due to fewer trees and more paved surfaces.

Even “a few degrees’ difference in temperature can be the determining factor between life or death for some city residents,” Catherine Harrison, a public health specialist, tells National Geographic. One 2011 study cited by the Times found that “a single degree increase in temperature during a heat wave can increase the risk of dying by 2.5 percent,” states a Smithsonian Magazine article.

These temperature disparities and their potentially deadly impacts highlight the immediate importance of accounting for highly localized temperature extremes in heat forecasts and warnings, and the longer-term need to mitigate extreme heat by planting trees and creating new green spaces. NOAA and its partners are mapping heat inequities in 11 states this summer as part of a larger effort that has mapped urban heat islands in many other communities in recent years.

“The mapping campaigns provide a roadmap to help communities alleviate these disparities by identifying specific locations where heat-mitigating interventions could save lives,” said Portland State University Climate Adaptation Professor Vivek Shandas.

4. Warmer Nights are Making Heat Waves More Deadly

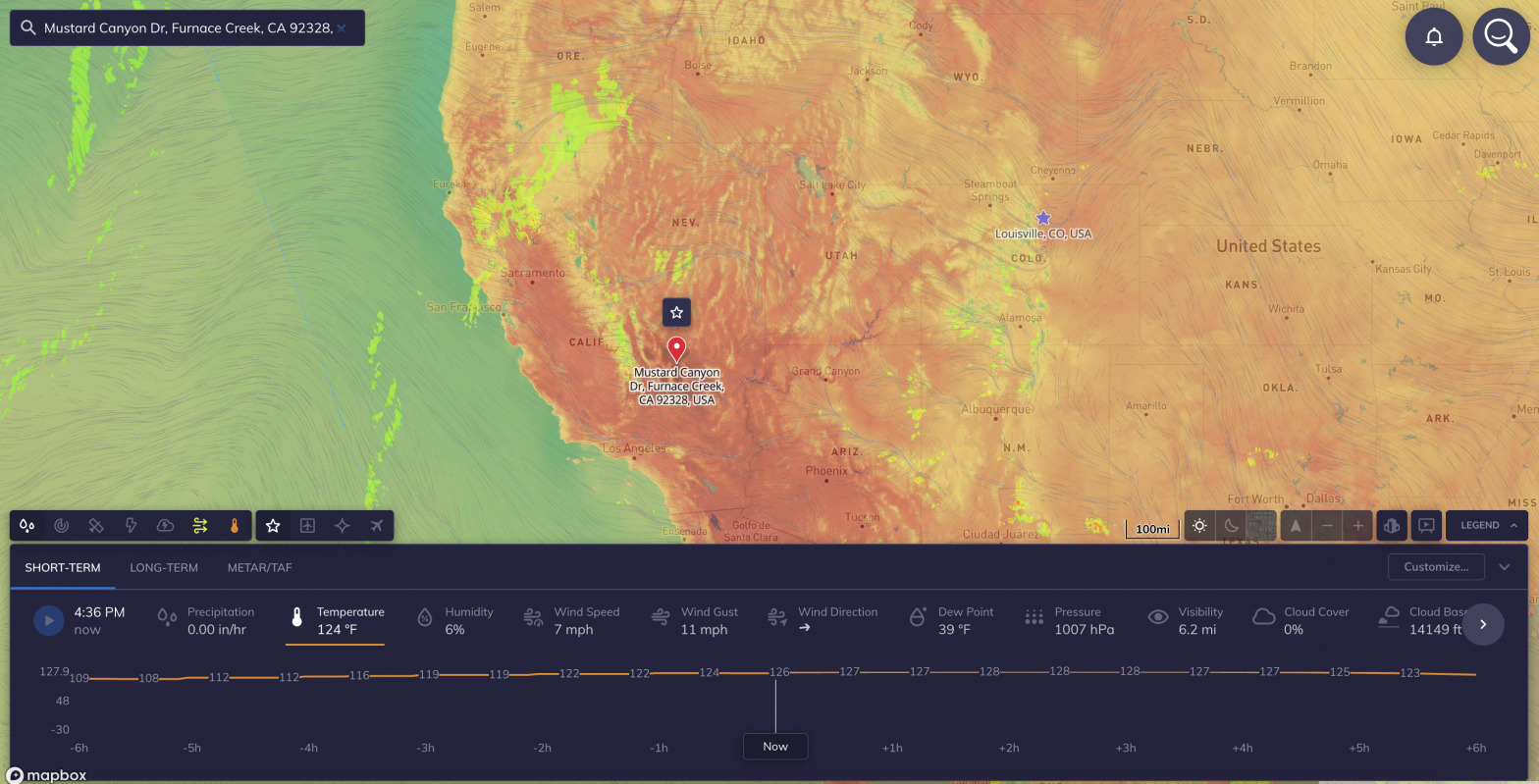

Sizzling high temperatures, such as the 130-degree reading in Death Valley, California on July 9, grab most of the headlines during heat waves. But warm nighttime temperatures can make heatwaves even deadlier by not allowing the core body temperature to cool off. City dwellers are even more vulnerable to warm nights due to the urban heat island effect, especially those without air conditioning.

Nights are actually warming faster than days across much of the planet, according to scientists at the University of Exeter, due to changing levels of cloud cover as the global climate becomes warmer and wetter. A recent New York Times article notes there were more nighttime temperature records this past June than any other June on record.

The article discusses a 2006 heatwave that led to nearly 150 deaths in California: “What made that particular heatwave dangerous was its humidity, which traps heat at night, resulting in unusually high nighttime temperatures that caught Californians off guard,” said Tarik Benmarhina, an environmental epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego.

So the next time hot weather is in the forecast, don’t just pay attention to the forecast daytime high temperatures. Even though heat warnings are typically only issued for peak daytime temperatures and humidity levels, it is warm nighttime lows (especially those around 80 degrees and higher) that can be as dangerous as daytime highs.

5. Looking Out for the Elderly

Like children, the elderly are especially vulnerable to extreme heat, which can kill not only by dehydration and heat stroke, but also by the exacerbation of pre-existing cardiac and respiratory problems. “Exposure to extreme indoor heat may be connected to a greater number of heat-related deaths than previously believed, especially among the elderly,” according to recent research on the impact of heat indoors.

By correlating indoor heat with emergency room admissions and mortality rates in Houston, a team of scientists led by the National Center for Atmospheric Research’s Cassandra O’Lenick found that “people living in lower-income neighborhoods that were predominantly nonwhite and had less central air conditioning faced the greatest risk of dying from health conditions caused by indoor heat.” Many elderly residents living on fixed incomes don’t have air conditioning or can’t afford to use it.

The National Institutes of Health recommends that older adults can lower their risk of heat-related illness by drinking plenty of liquids; avoiding alcohol and caffeine; limiting use of the oven; closing shades, blinds or curtains during the hottest part of the day; opening windows at night; and of course, checking the weather report before going outside. “During hot weather, think about making daily visits to older relatives and neighbors … offer to help them go someplace cool, such as air-conditioned malls, libraries, or senior centers.”

What’s next? A US Congressional Hearing on Extreme Heat

The dangerous heatwaves have led directly to the US government looking to take action and better understand how heatwaves impact business as well as individuals. The CEO of Tomorrow.io, Shimon Elkabetz, will testify before the House Science, Space and Technology Committee, Subcommittee on Environment on Wednesday at 10 AM to share insights on how extreme heat can impact business leaders everywhere.

Watch the hearing live.