This article originally appeared in The New Yorker on September 25, 2023.

In Boston, the weather-heads at Tomorrow.io, which does bespoke forecasting for companies like the N.F.L. and Delta, were never worried about Hurricane Lee.

On a recent Thursday, a hurricane was tracking toward the general vicinity of Boston. How dire was it? Headlines varied from “Hurricane Lee to Peak in the Boston Area Around 6 a.m. Saturday” (the Globe) to “Worst of Hurricane Lee to Miss Boston” (the Herald). What’s with all the confusion?

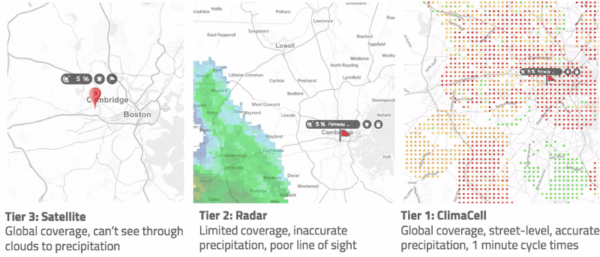

“This entire system”—the information gathered from ocean buoys, ground-based radar, weather stations, aircraft, satellites, and weather balloons—“has been predominantly done by government agencies,” Rei Goffer, a founder of the Boston-based weather-intelligence company Tomorrow.io, said, a few hours before the duelling newspaper reports. Everyone, it seems, swears by a weather app (one year’s AccuWeather craze is the next’s Dark Sky mania), but they all rely on the same limited info. “The Weather Company? Your iPhone? These are solely repackaging governmental data,” Goffer said. “They don’t really contribute anything to the effort.”

Image by The New Yorker

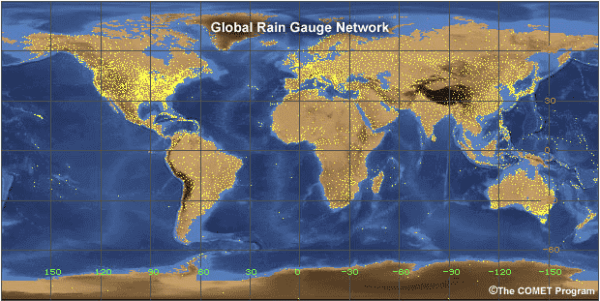

Earlier this year, in the spirit of contribution, Tomorrow sent two test weather-radar satellites into orbit on SpaceX Falcon 9s. The company is now planning to send a combination of radar and microwave sounders—twenty-eight in all—into space, to monitor most of the Earth every hour, instead of once every three days, which is the current rate for the radar aboard nasa’s billion-dollar Global Precipitation Measurement Core Observatory. Goffer pointed out that much of the globe isn’t covered at all by ground-based weather radar. “Those types of forecasts are almost as good as a toss of the coins!” he said. Tomorrow claims that its forecasts are thirty-eight per cent better than everyone else’s, thanks to an artificial intelligence that the company has nicknamed Gale.

Tomorrow already offers boutique weather services to clients including JetBlue, Delta, Uber, the N.F.L., Porsche, Ford, Live Nation, Denny’s, and the city of Hoboken. The company consults on questions like whether to promote ice cream or hot chocolate on a drive-through menu, when to expect employees to call in sick because the weather is too bad (or too good), and whether a singer can go onstage without getting struck by lightning. The U.S. Open uses Tomorrow to decide whether to keep its stadium roofs open. The company charges business customers as much as seven figures. (It also offers a free consumer app that tells you when it’s a good time to take your dog for a walk.)

Goffer, who is thirty-eight and has a scruffy beard, was on Zoom from Tel Aviv, where he lives. He was checking the news while fielding texts from friends in Boston seeking the storm scoop. “I tell them, ‘Use our app,’ ” he said. He declined to make his own predictions. “As far as safety and lifesaving weather alerts, the source is the government,” he said. The National Weather Service had just issued a warning of “significant threat to life or property” and a directive to “take action within the next hour.” Tomorrow’s app said that it was seventy-four degrees and sunny.

The following day, the governor, Maura Healey, declared a state of emergency and activated the National Guard. At the company’s office in Bourne, outside Boston, no one seemed concerned. “Hurricane Lee? No, not for us,” James Carswell, who helped design the technology for Tomorrow’s radar satellites, said.

Carswell, who is fifty-five, wore a light-blue polo shirt and braided bracelets. In his office, a whiteboard filled with enigmatic scribbles bore a sign that read “Caution Do Not Erase.” He’s the type of weather guy who flies in hurricane-chasing aircraft. “I probably have over one thousand hours in the actual storms,” Carswell said, adding, “These larger hurricanes, you need information over the entire globe, and technology hasn’t been there. The cost of going to space was just too expensive.”

Another issue that Tomorrow is trying to fix? The weather is often unintelligible. “A forecast will say, ‘Twenty-per-cent chance of rain, high winds across the state of New York,’ ” Dan Slagen, Tomorrow’s chief marketing officer, said. “Weather intelligence will say, ‘Stop the trains at mile marker twenty-seven, Thursday, at one o’clock.’ ” He said that a rep from one company told him, “I’d rather have one wrong forecast than multiple forecasts.”

Slagen and Carswell strolled down the hall and into a laboratory. “This was our original prototype of our Pathfinder radar system that’s up in space right now,” Carswell said, pointing to what looked like an R2-D2 autopsy. He said that the satellites for the next launch were the size of dorm-room fridges.

Outside, the weather was gloomy but not apocalyptic. (The storm did, ultimately, stay out in the Atlantic, before making landfall in Nova Scotia.) Was it hubris to think that we mortals could predict the future? “Weather is very chaotic,” Carswell said. “We always say, ‘Wait an hour in New England and it’s going to be different.’ ” ♦

This article has been updated with a revised list of Tomorrow.io’s public clients.