When most people think of meteorology, they think of forecasts which make useful predictions: Is it going to rain this afternoon? Do I need to fix my air conditioner before this upcoming heat wave? Is a frost going to kill my vegetable garden tomorrow night?

But a forecast can only be as good as the data that goes into it – namely, observations of the current weather. As a result, meteorologists and weather watchers have long been partners. In the mid-1800’s, the invention of the telegraph allowed the Smithsonian Institution to collect weather reports from across the United States. These reports proved so useful for anticipating weather in the Great Lakes and on the Atlantic coast that President Grant authorized the Signal Service Corps (part of the Army) to begin coordinating synchronous reports in 1870.

These early weather reports were useful but quite limited. They only summarized broad changes in pressure, temperature, humidity, winds, and clouds, as well as a short description of the weather. Data was telegraphed to a central location at best once per day. However, this infrastructure provided the foundation for what would later become the National Weather Service and a much larger-scale effort to monitor the atmosphere and predict the weather.

Fast-forward to the present…

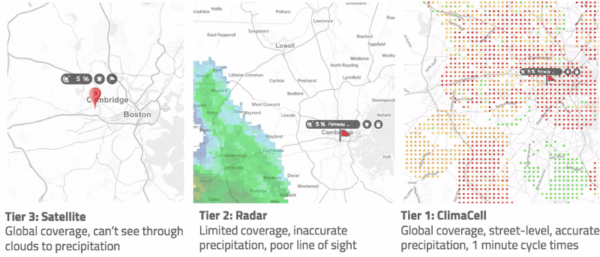

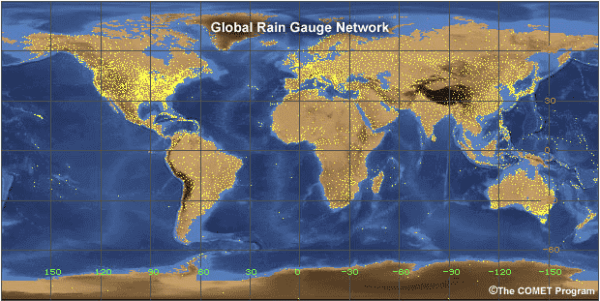

Today, meteorologists have a plethora of tools to probe the state of the atmosphere, from weather balloons and automated observation stations to radars and monitoring devices installed at the ground, on airplanes, and in the satellite orbiting the Earth. Yet, some measurements still elude us. For instance, have you ever noticed that it was drizzling or raining, yet nothing was popping up on the radar app you installed on your phone? Each tool we use to monitor the atmosphere has advantages but also limitations: satellites offer a nearly global view, but often can’t see through clouds or may be limited to one picture per 12 hours; doppler radars can rapidly scan the horizon, but can’t see what’s happening near the surface; even the densest observation networks may only offer one measurement per several square kilometers.

Enter Tomorrow.io. To better monitor the atmosphere, we’re bringing online cutting-edge observation systems and using them to improve real-time analyses. And we’re already seeing a difference when it comes to detecting weather events that give traditional systems a hard time.

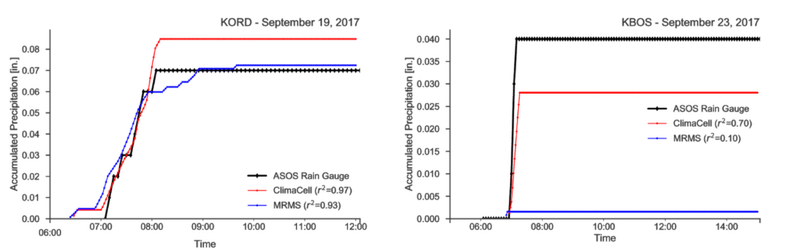

Figure 1) Time Series of light rain/drizzle accumulation at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago (KORD) and Logan International Airport in Boston (KBOS) compared between the official observations (ASOS Rain Gauge), the Multi-Radar/Multi-Sensor System (MRMS), and Tomorrow.io’s unique observations (Tomorrow.io). The r2 score here estimates the correlation between the MRMS/Tomorrow.io data and the rain gauge time series.

In terms of the weather, the best-observed places in the world are major American air terminals. These sites have automated observation systems, on-site doppler radars (on the tower and in airplanes taking off and landing), and human observers who can make corrections when instruments go awry. You can imagine why we test our observation systems against the data collected at airports!

In Figure 1 we show time series of precipitation accumulation during light drizzle events at two different major American airports back in late September. In one case, we performed as well as the state-of-the-science MRMS system from the National Severe Storms Laboratory, even capturing the end of the rain about an hour earlier. In another case, we were able to more accurately gauge the amount of rainfall that accumulated during a misty, drizzly Boston morning. Usually, under these conditions (which are really common during the late Summer and Fall!) traditional radars fail to capture the drizzle, which can pose a real hazard during the colder months when the drizzle freezes to concrete and metal surfaces on contact. But we’re able to detect these phenomena in real-time before pilots notice ice accumulating on their aircraft’s control surfaces.

We’re excited to be revealing the weather in greater detail than ever before!

Author: Daniel Rothenberg ([email protected])

Last Revised: October 17, 2017