Hurricane season brings high winds, heavy rain, and scientific discovery.

I recently had the chance to speak with Clayton Bjorland, Senior Radar Scientist at Tomorrow.io, about his thrilling experience flying into the core of massive storms with NOAA’s Hurricane Hunter team.

Alongside a team of twenty, including NOAA scientists and flight crew, Clayton spent 8 hours on board NOAA WP-3 N42RF, nicknamed “Kermit,” as they did five passes as close to the center of the eye of Hurricane Lee.

Check out the video below to learn more about his experience on the flight.

Collecting Data in the Eye of the Storm

The Hurricane Hunters are specialized aircraft and team within NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center in Lakeland, Florida. As Clayton described:

“What you see on the TV or read in the news, those forecasts typically come in the U.S. almost solely from the National Hurricane Center, and that’s a division within NOAA and the National Weather Service.”

Their mission is to fly directly into the eyes of hurricanes and collect weather data critical for forecasts and warnings from the NHC. The only way for NOAA to get hurricane weather data is to collect it by aircraft and satellite when available.

According to Clayton, these flights last 6-8 hours, with several passes through the eye of the storm. He described the turbulent conditions on board:

“It’s bumpy; that’s the truth. But the plane is really solid. And the pilots are really good, and you have this sense of safety, even though the plane is bouncing around.”

Analyzing Data in Harsh Conditions

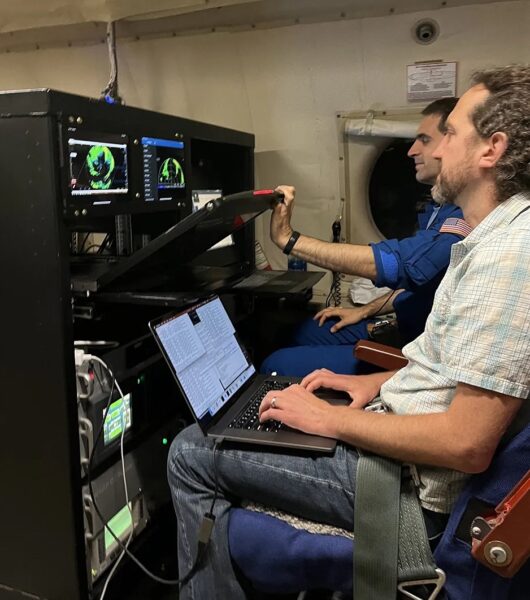

Clayton Bjorland Onboard NOAA WP-3 N42RF via Axios

While being jostled around in turbulence, Clayton and other scientists work hard to operate their instruments and analyze incoming weather data.

Typically, NOAA collects data on the storm’s location, trajectory, and internal structure. On this flight, Clayton’s role was working with the NOAA NESDIS Star Team, where they operated two instruments: KaIA and IWRAP.

KaIA is an altimeter measuring significant wave height, while IWRAP is a conically scanning radar that measures Doppler wind speeds from that aircraft down the ocean surface.

According to Clayton, “These instruments both use Tomorrow.io ARENA software-defined radars, and there’s code that I’ve worked on that runs in real-time, processing the data. To make the retrievals for the wind speeds on IWRAP.”

KaAI and IWRAP complement the other instruments on the aircraft, providing measurements not made by the tail Doppler radar or SFMR. IWRAP provides a look at the vector field of wind factors going down to the ocean.

Both instruments provide several data points that weren’t previously available, helping to paint a complete picture of the storm and informing models and forecasts that predict sea state and storm surge.

This data gives forecasters a detailed look at storms like Hurricane Lee. The aircraft instruments work together with satellites to build a complete picture and provide the data to the meteorologists who need it.

Rewarding Collaboration Amid Challenges

These flights are rough on the team. Clayton shares that the most challenging part of being on these flights is the turbulent work conditions, “You have to think about what you eat, you have to think about how much water you’re drinking…”

But these adventures certainly are rewarding. For Clayton, the most rewarding part of these perilous flights is collaborating with researchers from NOAA’s Environmental Sciences Division, “They’re insightful researchers, and it’s really interesting to talk about all the details of the measurements of the storms.”

Their teamwork amid the challenges of extensive travel and harsh flying conditions leads to scientific insights that can help protect lives and property when hurricanes strike.

Conclusion

Rare chances to collect data inside the eyes of hurricanes advance meteorology and our fundamental understanding of these immense, destructive, and spectacular storms. Hats off to the brave Hurricane Hunters, who are helping to tame nature’s fury through scientific discovery.