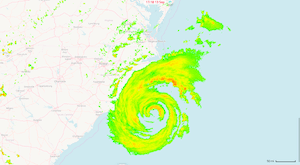

While our focus here at Tomorrow.io is MicroWeather and not tropical cyclones, we are all currently very focused on Florence. In terms of sheer size, Florence is 1.5X larger than the average hurricane with hurricane force winds stretching out up to 75-80 nm from its center, and tropical storm force winds extending up to 185-200 nm from the center. The National Hurricane Center forecasts Florence to maintain Category 2 intensity up to landfall, but this may downplay the potential for damage from this storm if the general public does not dig into more details of the story. Often, there is too much focus on the maximum sustained winds to describe hurricane severity, when in fact, the radius of hurricane force winds is a much better indicator of coastal damage potential (related both directly to wind impacts and storm surge inundation), and the total precipitation accumulation is the primary inland danger, driving flash flooding and river flooding.

What are the biggest risks associated with the landfall of a hurricane of this size?

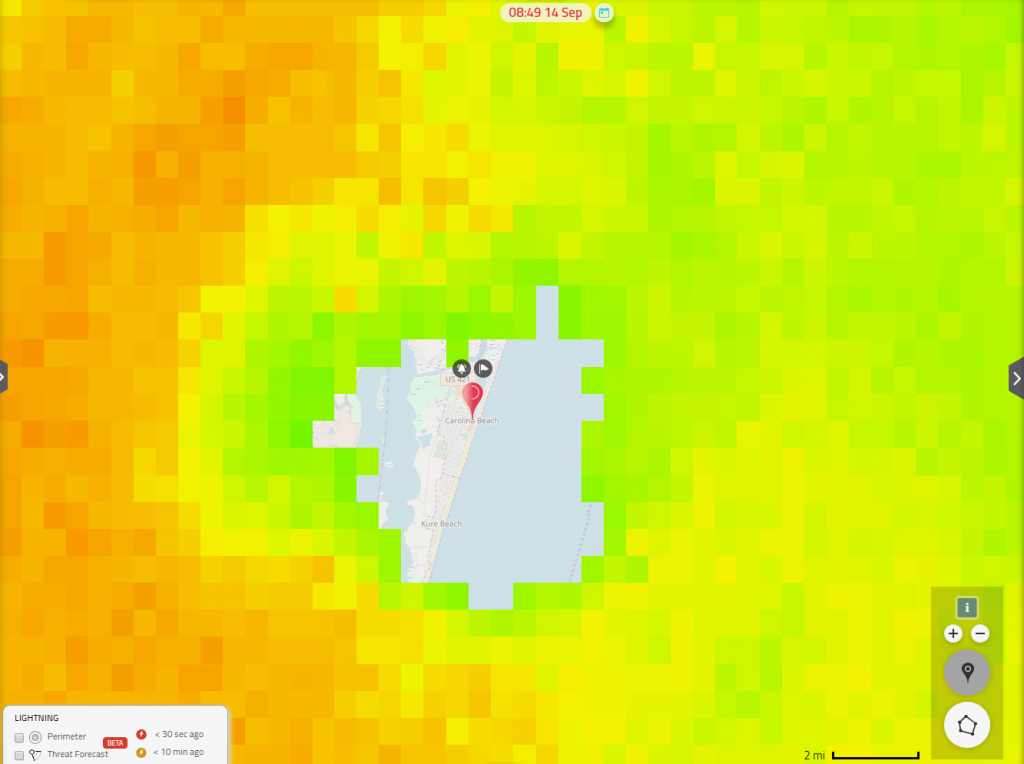

Looking past wind damage potential near the eye during landfall, we need to consider the potential for storm surge and the five-day precipitation forecast. Over the last 12-18 hours, the inner core of the storm has deteriorated due to dry air entrainment, but the wind field is quite large with a long E/SE fetch (which means danger of a big surge over an extended stretch of the coastline, as the water piled up by the surface wind flow around the storm moves into the coastline). Wilmington is already experiencing almost 6 feet of surge, and the storm is still 100 nautical miles away.

The large tropical moisture plume + slow motion + upslope flow into the terrain of the Carolinas will yield very efficient and prolonged precipitation production. The latest models project upwards of 2 feet of rain in parts of eastern and southern North Carolina, and eastern South Carolina, shattering existing state-wide records. Florence is likely to bring rain to the Carolinas through Sunday, providing plenty of time for rain to accumulate, resulting in saturated soils and a major flooding threat.

What causes a hurricane to stall at the coast?

Collapsing steering currents lead to the stall (weak vertically integrated flow); the ridge from the eastern Midwest to the west Atlantic is somewhat 2-celled aloft, creating a relative weakness in the flow field near the NC coast.

Yes, the stall is quite bad for flooding implications. It maintains high rain rates and sustained influx of tropical moisture into east and northeast North Carolina. The coast lines will also take a prolonged beating with multiple high tidal cycle storm surge enhancement periods…..unfortunately, with the slow motion near the coast, this surge is not a “one and done” event.

More resources:

- National Hurricane Center

- Hurricane Florence is Dangerous. Why Some People Won’t Leave (Dr. Marshall Shepherd)

- Google Crisis Map